Premium HDMI Cable Benefits

Truth Versus Fiction and How To Choose

Shown here is the Audio Authority HS-HDMI-Series Cable, an example of good bang-for-the-buck. It is rated "High Speed with Ethernet".

HDMI Truths

by Mark Schneider

There is no shortage of opinion on the value of premium HDMI cables, many written by people who's main goal seems to be to debunk overpriced HDMI cables. The trouble is that, in their enthusiasm for consumer protection, some important points are being lost.

First of all, I will agree that there is very little reason to spend thousands of dollars for an HDMI cable - on that much, most sensible and informed people can agree. But to say that all HDMI cables are the same...that it doesn't make any difference at all...well, that simply isn't true. I have seen $5 HDMI cables that were so poorly made that they didn't work at all, right out of the package. I have seen failure rates as high as 30 percent. Those cables never even made it onto our website. Conversely, I have seen intermittent system issues solved by replacing multi-hundred dollar HDMI cables with "sanely-priced" ones.

And honestly, the standards and testing system that is currently in place just doesn't help very much. First of all, getting a cable certified is quite expensive. Something like $160,000 per cable. It's so expensive that some vendors don't do it at all. And the ones that do, typically only do it for certain lengths within a given series of cables. Then they just imply that the entire series is "High Speed with Ethernet", or whatever the certification was that they got for some particular length within that series. So the 2 meter length might be certified, but longer ones are not. Meaning that one cannot expect a 15 meter cable to perform the same way as a 2 meter cable. All else being equal, physics demands that shorter cables will accommodate more bandwidth than longer cables. That's just the the way it is. There are some schemes to cheat physics, such as using larger/better cables for the longer lengths, and there are also active designs that can help with longer distances, but then active cables come with their own set compromises.

To make things even more confusing, many times the certification is associated with the actual manufacturer, as opposed to the seller. For example, many well-known US-based companies buy HDMI cables from manufacturers in China, so the certification(s), if any, are awarded to the manufacturer, not the seller. Since buyers typically have no way to know the name of the company that actually manufactured a given cable, one can't even go and look up the certification to find out exactly what was certified. Given the high cost of certification, all of this is to be expected. It seems that the the process is more about perpetuation of the certification industry than it is about giving consumers useful information. If the price was right, then everyone who makes worthy cables would get all lengths certified, and that would actually help buyers.

But that's not how it works at the time of this writing, so unfortunately, certifications, and in particular, claims of certification, are not very helpful. What a buyer would really like to know is the actual performance potential of a given cable. In my mind, it would make an awful lot more sense to grade performance in terms of maximum bandwidth. That way, one could easily look up the bandwidth requirements for, say 4K 2160p with a 60 Hz refresh rate and 4-2:0 sampling, then go shop for a cable that exceeds those requirements.

It would be a lot like shopping for light bulbs in the incandescent era. If one needed 850 lumens, then one could just buy a 60 watt bulb. 1700 lumens? Buy a 100 watt bulb. Even light bulbs aren't so simple anymore...one buys a bulb labeled as "60 watts", but it only uses 43 watts, which seems good until one notices that with a rating of 750 lumens, it's also a 100 lumens dimmer than the bulb it was intended to replace. And while they don't say so on the package, the underlying technology is tungsten-halogen, so the there is more UV and the color temperature is not quite the same either. This is relevant only in that this sort of dumbed-down standards, labeling, and marketing mentality makes it much harder than it needs to be to make informed purchasing decisions. This same attitude permeates multiple markets with similar results. Like smart phones that are so advanced that they "just work". Until they don't. Or HDMI cables that are so easy to buy that all one needs to look for is any cables that is labeled "High Speed". That would be nice.

Most people are not aware that cables that carry no certifications can work just as well as cables that do. Or that advanced HDMI features are more about the connected equipment than the physical cables that connect that equipment. The reality is that some very good HDMI cables that were created before the existence of UHD, 4K, or even 1080p work just fine with the new resolutions and features. At the end of the day, it comes down to bandwidth, and as long as a given cable accommodates the required bandwidth, the HDMI versions and sub-versions don't make very much difference. Which really does make it harder than it needs to be to select a cable.

As it stands today, we have less information than we need in order to make good HDMI cable purchasing decisions, so we must rely on other information. For example, do we trust the seller? At Cables Solutions, we do have a number of customers who have come to trust us because we have never sold them a cable that didn't work flawlessly for the intended application. One might also turn to trusted brand names, but with brands being bought and sold as often as they are, brand names mean less than they used to. And even within brands that have not changed hands, it can be hard to know what you'll get. For example, a television manufacturer might source LCD panels from multiple manufacturers, and then use all of the different panels interchangeably in the same model TV. So even if one went to the trouble to read reviews before buying, there is no reason to believe that one would get the same panel as the one in the TV that was reviewed. Maddening.

If you have read this far, then you're probably expecting a conclusion, or at least some advice. I regret that I don't have any perfect answers. I can offer that if you buy a cable from us, then you can have some confidence that it will work as advertised, because we don't sell any cables that don't work as advertised. Assuming that you believe me to be truthful, that is. And granted, I do not qualify as a disinterested third party, so you might consider this - a great many cables are made in China. Even the best ones. The range of quality varies quite a bit, but there is one thing that seems to remain consistent, and that is that (in my experience) the very cheapest cables typically cause the most problems. With that simple fact in mind, my best advice would be to avoid shopping at the bottom end. Paying a high price may not guarantee high performance, but low price certainly can be related to low performance. So there is that.

With HDMI cables, there is a very thin margin between acceptable and unacceptable. For example, with analog video cables, degradation is gradual and predictable. Assuming a good cables, component video might look worse at 100 feet than it does at 10 feet, but it still looks fine. If you couldn'tperf compare the images side by side, you'd probably never notice the difference. We've done runs over 500 feet, and while the video quality did suffer to some extent, it was still perfectly acceptable for most purposes.

That's not how it works with HDMI. By comparison, it is a fragile interface, both mechanically and electrically. At high resolutions and frame rates, common HDMI cables work fine at 3 meters (10 feet), but wouldn't work at all at 30 meters (100 feet). And the degradation is drastic and unpredictable. If one could try cables out, adding one meter at a time, one might observe a perfect picture at 8 meters, "issues" at 9 meters and no picture at all at 10 meters. It goes almost straight from perfect to bad, and even faster from bad to non-existent. That is the nature of digital signals. It will look perfect right up to the point that the decoder can no longer detect the digital waveform, but at that point, it will fail catastrophically. If you want to read up on it, search the Internet for "HDMI eye pattern".

This is almost certainly the reason that any number of authors have been prompted to write that there is no difference between HDMI cables. And within a certain range of acceptability, it is true. But in the real world, there are many factors that can affect that range. For example, the weak point of any cable is typically the interface between the cable and the connector. It's more of a problem for HDMI cables than for more traditional signal cables because with HDMI, there is more than one cable "channel" hidden beneath the jacket. When the cable is bent, the channels on the outside of the bend are stretched while the channels on the inside of the bend are crumpled together. Most HDMI cables employ foil shielding, and foil doesn't respond well to stretching and crumpling. Simple bending can break conductors, break or deform the shielding, short-circuit at the connector, and even rip pins right out of the connector housing. It is less of a problem in the middle part of the run because the bundled channels are often twisted into a spiral, so where there is some length to work with, the stresses tend to offset each other. But at the connectors, there is not enough room for the spiral geometry to offset the stresses, making that the most common point of failure.

Something that most people have never done is to cut an HDMI connector open. I have. I think most people would be surprised to see how it looks. First, most HDMI connectors that I have cut open were obviously hand assembled. This is not what one would expect to find in this age of mass production. And it's kind of a mess in there. They must have lots of people with small hands soldering connectors onto HDMI cables because the connectors are physically small. The cable prep and solder were not consistent. There are definitely varying levels of design quality, expertise, and quality control. They are not all the same. Not by a long shot. A connector that has a lovely over-mold may have a dreadful design and ugly assembly work inside. With the shoddy designs and workmanship, it's not surprising that so many HDMI cables fail at the connectors. And this certainly supports my own observation that just because a cable works okay when it's first hooked up, that doesn't mean it will keep working the same way.

More expensive cables can afford to employ better materials, connector designs, and better assembly techniques, so even if the skill of the assemblers is the same, they still have a better chance of producing a good result. And then there is the cable itself. Some cables are more flexible, making them easier to work with and more resistant to failure. Some have superior internal geometry, which helps reduce flex-related failures. Some have the materials properly stabilized so that they don't deform during assembly and/or stiffen over time. So while it may be true that a cheap cable will perform the same way as a high-quality cable when initially tested, that doesn't mean that they are actually equal.

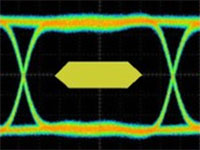

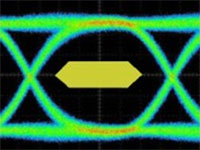

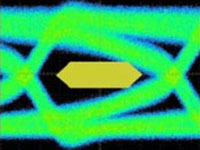

And then there is that threshold of failure that I mentioned above. Take a look at the eye patterns at the upper right. It's clear to see the that the top example has a great deal more headroom than the bottom one. We could probably get by with the middle one, but what we really want is the top one, because that one has plenty of performance to ensure that that the bandwidth will remain well above the threshold. This threshold is often referred to as the "cliff effect" in technical papers because once the critical threshold is reached, it's like the signal just falls off a cliff. A cable that barely performs above that threshold when new may not do so over time.

Flexing hurts the performance of any cable, and some much more than others. And let's face it - there is no way to install a cable without flexing it to some extent. Just the weight of the cable hanging on the connector can produce enough stress over time to cause a failure. Environmental EM also conspires to reduce performance. And EM interference can be transient, causing a cable that worked when first installed to stop working. Or to fail intermittently. The take-away is that it is best to use a cable that has some bandwidth overhead. It needs to be good enough so that even if it degrades to some extent, the signal quality will remain above the required threshold. We need that "eye" to remain wide open. Good quality cable, well-designed connectors, good termination techniques and good quality control all contribute to trouble-free HDMI hook-ups.

So you see, all HDMI cables are the same. Until they're not. To recap, my best advice is to buy from someone you trust. Beyond that, avoid the cheapest cables. You don't have to get crazy, but at the same time, don't be afraid to spend a few extra bucks on quality. You might also take a clue from professional installers. For example, the the origin of Audio Authority's HS-Series High Speed HDMI Cables with Ethernet was that they needed some HDMI cables that were good enough to use in their own retail demonstration installations. And good enough for their professional integrators and installers, but not too expensive. They are not the cheapest HDMI cables in the world, but they are certainly modest, by most standards. And they have proven, over many professional installations, to be reliable. That's why we continue to offer them. We might not recommend the longest lengths for the highest bandwidth installations, but they're good basic, professional-quality cables.

As always, if you need some help, please don't hesitate to contact us!

Here is a link to our HDMI cable offerings.

Shown here is near ideal eye pattern test. This HDMI cable easily out-performs the ones shown below.

Here is the same signal with a second cable. This cable would pass the test, but is obviously inferior to the first one.

This eye pattern represents the same signal again, but with a third cable. This cable would not pass the test. It might work with some equipment combinations, but it is so close to "the cliff", or threshold of failure, that anything could push it over the edge.

Interestingly, if one were to hook this cable up, and it happened to work, one might assume it to be equal to the other two cables, but this image graphically demonstrates that to be an incorrect assumption.